Año: 2018

The Round by Chus Tudelilla

On December 4, 1924, the film Entr’acte by René Clair was premiered at the Theater des Champs-Élysées in Paris, during the intermission of the dance show Relâche. Picabia, author of the sets, had commissioned René Clair to direct the film based on some ideas that he had passed on written on a sheet of paper from Maxim’s. After seeing the film, a masterpiece of Dada cinema, Picabia declared: "Entr’acte is a true intermission, an intermission to the boredom of monotonous life and to conventions full of hypocritical and ridiculous respect." Around four minutes from the beginning comes the scene filmed from the roof of the theater in which Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp, sitting on the edge of a parapet, chat and play chess, a game in which, according to Duchamp, "you kill, but you don’t kill much."

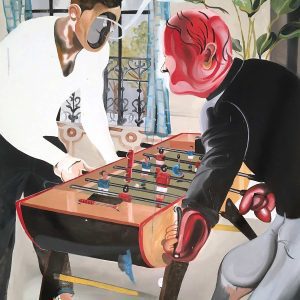

This exercise of "killing peacefully" may have served as therapy when they were beleaguered by two world wars, says Larry List, for whom chess also provided guidelines on which to improvise in art and in life, helped them establish new relationships between the work of art and the viewer –"The artist spoke and the viewer listened […] It was an affirmation, and now […] it's a dialogue!", exclaimed Duchamp–; and he showed them a new particular conception of pictorial and spatial organization. In the disconcerting juxtaposition of Entr’acte images, there is no lack of boxing gloves. The chess board and the boxing ring are the new settings for Yann Leto's last paintings, in addition to tables for armwrestling and table tennis. Settings that share, somehow by means of the interaction of movements of those who practice in them, the possibility of planning the abstract. "The ring is like the painter's white canvas: total lighting… exacerbated! The ring is an illuminated painting, designed to create tension while being also a place of tension.

Everything can happen there and everything must happen. Almost the same as in a painting. There are the drama, the joy, the pain, the humiliated people, the surprise, the wet towel that flies, the water, the resin, the blood..." Eduardo Arroyo wrote in his book Sardines in oil. I imagine Yann Leto has read and knows Eduardo Arroyo's works well. His paintings reveal so. Of Al Brown, Arroyo says that just as the painter always thinks of his hands, he too was obsessed with his and with blindness; his hands always hurt, and when he KOed his opponent it was to prevent him from suffering too much and to ease his own pain. For one boxer’s suffering is linked to the punishment of another. A new exercise in "killing peacefully". Milou Pladner faced blindness. He lived for forty years in darkness, but boxing, he declared, allowed him to live the extraordinary adventure of seeing the world and exciting the audience.

Yann Leto paints what is close to him, it is his way of intervening actively. He seeks recognition and complicity with the audience targeted by his paintings: boards in which he quotes great avant-garde artists, whose presence appears liquefied in the uninhibited, grotesque, distorted and dissonant, exasperating, cannibalistic, strange, claustrophobic, maddening, delusional, gestural and loud chromatic episodes which persevere in their narrative secrecy. Of Poe, Benjamin wrote that his discomfort with society made him seek out the crowd to hide; and to blur, on purpose, the difference between the flâneur and the asocial, since the harder to find, the more suspicious among the crowd a man becomes.

Leto, like Poe, is a man of crowds. A position he chooses not to hide but to experience live what he sees. "The most political thing I can do is to interpret people's lives, including my own, in a way that arouses interest, empathy, questioning, or even antipathy for what they are seeing, but somehow commits them to watching life as it is really lived and to react to it." I quote David Shields, specifically section 144 of letter e, which attends to reality, in his essay Hunger for Reality. A manifesto. And although he did not know them, Yann Leto seems to follow in his works some of the instructions for painting the great city that Ludwig Meider published in 1914: the first task was "to learn to see, in a more intense and correct way than our predecessors", and the second, to paint "life in its fullness: space, light, darkness, heaviness, lightness and the movement of things." In short, "to penetrate more deeply into reality"; to conclude: "Let's paint what is close to us, our urban world…!"